How at Ultralytics we make YOLO models faster on your favorite chip

How Ultralytics optimizes YOLO models for speed across CPUs, GPUs, and edge devices. We'll explain chips, memory, and smart techniques like quantization, fusion, and pruning.

How Ultralytics optimizes YOLO models for speed across CPUs, GPUs, and edge devices. We'll explain chips, memory, and smart techniques like quantization, fusion, and pruning.

At Ultralytics, we make computer vision models; basically, we teach computers to see! Think of these models as giant mathematical recipes. They're made up of operations (we call them layers) and a massive pile of numbers that we call weights.

Our Ultralytics YOLO models process images as what they truly are: arrays of numbers! Each pixel is really just color values, the amount of Red, Green, and Blue (thus RGB) for every single point that composes the image. We call these number arrays "tensors" because it sounds way cooler than "multidimensional matrices," which sounds way cooler than "numbers stacked on numbers stacked on numbers."

When you feed an image into our model, it goes on an epic journey through the network. Picture your tensor surfing through layer after layer, getting transformed, convoluted, and mathematically mangled in the most beautiful way possible. Think of it like a dance party where numbers mix and mingle, extracting the essence of what makes a cat a cat or a car a car. We call this process feature extraction.

What comes out the other end? More numbers! Meaningful numbers. In detection tasks, they tell you exactly where stuff is in your image and what that stuff probably is. "Hey, there's a 95% chance that's a dog at coordinates (x, y)!" We call this magical process inference.

Now, before our models can work their magic, they need to go to school; they need to be trained. The training part is where things get intense.

During training, every time we present the network with an image, we're not just getting an answer. We're doing two extra-heavy things. First, we compute how wrong the network was (we call it loss, basically the distance from the bullseye). Second, and this is the important part, we update every single number (or weight) in the network based on that loss. Think of it like tuning thousands of tiny knobs all at once, where each adjustment is calculated to make the network more accurate each time. We're essentially training the network through correction: every mistake teaches it what NOT to do, and we tweak all those weights so that when it sees a similar image again, it'll get closer to the right answer. Essentially, the network learns by getting nudged in the right direction, mistake by mistake, until it starts nailing the predictions.

How many numbers are we talking about? Well, our cute little YOLO11n has a few million parameters. But YOLO11x? That bad boy is rocking over 50 million parameters! More parameters mean more details you can encode, like the difference between drawing with crayons versus having a full artist's palette.

During inference, this parameter count becomes crucial. Running a 3-million-parameter network is like jogging around the block. Running a 50-million-parameter network? That's more like running a marathon while juggling flaming torches.

So what IS computation exactly? How does all this number-crunching actually happen? How do we make it faster? And what does "optimizing computation" even mean?

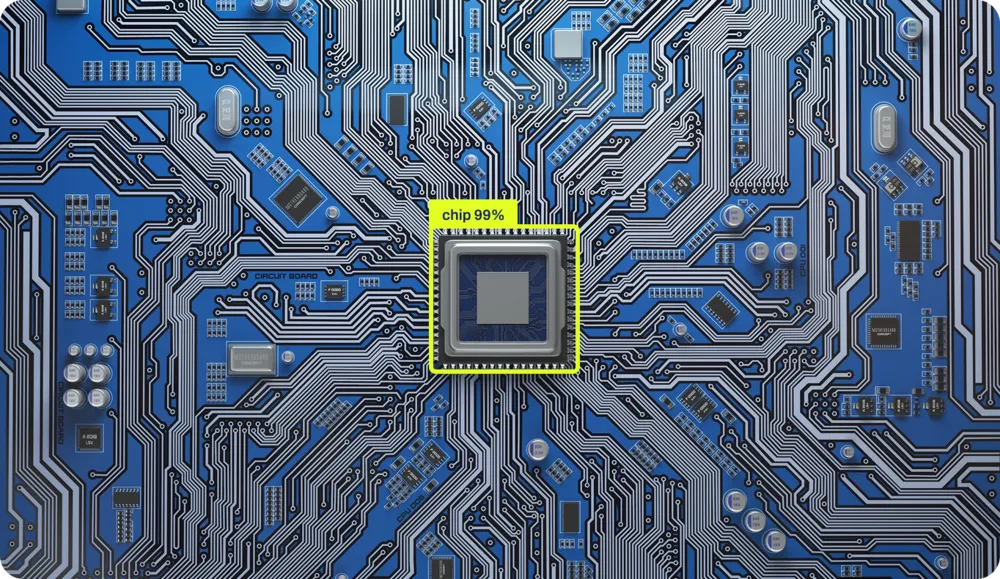

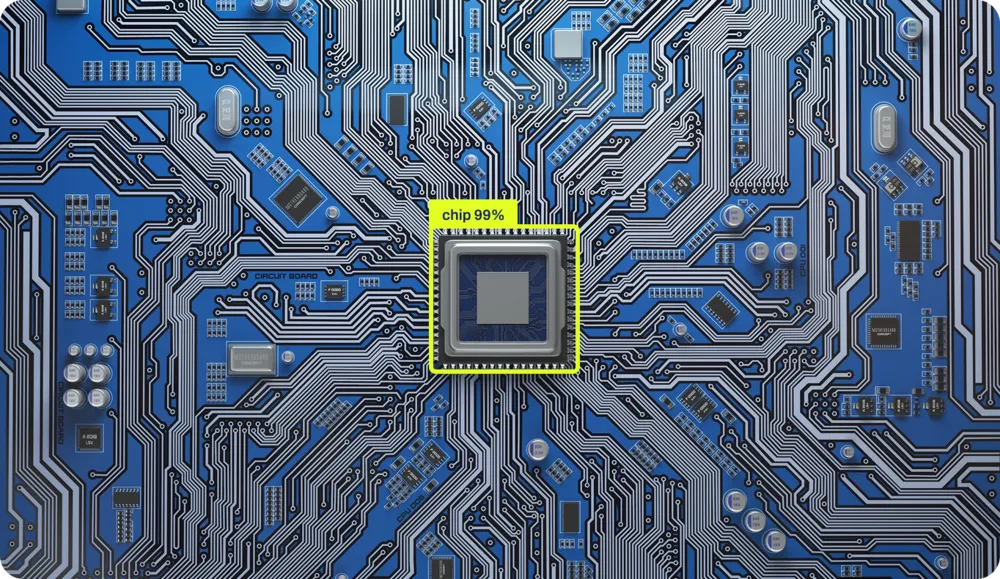

Computation happens with chips. These little squares of silicon are basically the universe's most organized sand castles. Every single operation your computer does, every addition, every comparison, every "if this then that", is physically carved into the silicon. There are actual physical circuits in specific areas of the chip dedicated to adding numbers, and others for logic operations. It's like having a tiny city where different neighborhoods specialize in different types of math.

This probably sounds bizarre, even if you're a computer scientist. That's because we've spent the last 40 years building layer upon layer of abstraction, like a technological lasagna that's gotten so tall we can't even see the bottom plate anymore. We've simplified things so much that most programmers today have no idea how computation actually happens in silicon. Not by fault of their own, but by design!

Let's peel back these layers. Take this dead-simple Python code:

x = 1

if x == 1:

y = x + 1We're making a variable x, setting it to 1, and if x equals 1 (spoiler: it does), we create y with the value of x plus 1. Three lines. Easy.

But here's where it gets interesting. Between those three innocent lines and actual electrons moving through silicon, there are AT LEAST four massive layers of translation happening (there are actually more, but our Digital Content Manager says my word count is already giving her anxiety). Let me walk you through this mind-bending journey:

Layer 1: Python → Bytecode First, Python reads your code and compiles it to something called bytecode, an intermediate language that's easier for computers to digest but would make your eyes bleed if you tried to read it.

Layer 2: Bytecode → Machine Code The Python interpreter (like CPython) takes that bytecode and translates it into machine code, the actual instructions your processor understands. This is where your elegant "if x == 1" becomes something like "LOAD register, COMPARE register, JUMP if zero flag set."

Layer 3: Machine Code → Microcode Plot twist! Modern processors don't even execute machine code directly. They break it down further into microcode, even tinier operations that the chip's internal components can handle. Your single "ADD" instruction might become multiple micro-operations.

Layer 4: Microcode → Physical Electronics Finally, we hit silicon. Those micro-operations trigger actual electrical signals that flow through transistors. Billions of tiny switches flip on and off, electrons dance through carefully designed pathways, and somehow, magically, 1 + 1 becomes 2.

Each layer exists to hide the insane complexity of the layer below it. It's like those Russian nesting dolls, except each doll is speaking a completely different language, and the smallest doll is literally made of lightning trapped in sand.

The irony? Those three lines of Python probably trigger MILLIONS of transistor switches. But thanks to these abstractions, you don't need to think about any of that. You simply write "y = x + 1" and trust that somewhere, deep in the silicon, the magic happens.

Every single operation is physically implemented in the silicon, and WHERE it happens on the chip depends entirely on the chip's topology. It's like city planning, but for electrons. The adder lives here, the multiplier lives there, and they all need to talk to each other efficiently.

We've got hundreds of different chips on the market, each designed for different purposes. What changes between them? The topology, how operations are positioned and implemented in the physical domain. This is what we call architecture, and boy, do we have a lot of them:

Each architecture not only arranges its transistors differently but also speaks a different language. The abstractions we use to send instructions to these machines are completely different. It's like having to write travel directions for someone, but depending on their car, you might need to write in French, Mandarin, or interpretive dance.

The fuel of our chips is electrons, electricity that flows into the chip, providing the energy for computation. But energy alone isn't enough. For a chip to actually work, to move data through its intricate topology, everything depends on one critical component: the clock. This is what makes electrons flow through specific paths at specific times. Without it, you'd just have powered silicon doing nothing.

Imagine trying to coordinate a massive performance where billions of components need to move in perfect sync. Without a beat, it would be chaos. That's exactly what the clock does for your processor. It's a crystal that vibrates at an incredibly consistent rate, sending out electrical pulses billions of times per second.

When you hear "3.5 GHz processor," that GHz (gigahertz) is the clock speed, 3.5 billion beats per second. Every beat is called a clock cycle, and it's the fundamental unit of time in computing.

NOTHING happens between clock cycles. The entire computer freezes, waiting for the next beat. It's like the universe's most extreme game of red light, green light. On each "green light" (clock pulse):

Some operations take one cycle (a simple addition), while others take many cycles (a division or fetching data from RAM). It's precisely choreographed, billions of components performing their specific operations, all synchronized to this relentless beat.

You can overclock your processor by making the crystal vibrate faster; everything happens faster, but it also generates more heat, becoming less stable. Push it too far, and your computer crashes because the electrons literally can't keep up with the beat.

Back in the day, these operations were implemented with machines the size of rooms. But the components that do all this computation are remarkably simple: they're just switches. On-or-off switches.

Wire enough of these switches together in the right pattern, and you've got computation. The entire digital revolution comes down to a sophisticated switch arrangement.

This simplicity means that if you have switches, any switches, you can build a computer. People have built functioning computers out of water pipes and valves, dominoes, LEGO blocks, marbles, and even with redstone in Minecraft.

The principles haven't changed since the 1940s. We've just gotten incredibly good at making switches extremely small. Your phone has more computational power than all the computers that sent humans to the moon, and it fits in your pocket because we figured out how to make switches at the atomic scale.

When we're running neural networks with millions of parameters, we're flipping these tiny switches billions of times per second, all perfectly synchronized to that crystal heartbeat. Every weight update, every matrix multiplication, every activation function, they all march to the beat of the clock.

No wonder training models makes your computer sound like it's trying to achieve liftoff!

Alright, so we've got these chips with billions of switches dancing to a crystal's beat, and we want to run neural networks with millions of parameters on them. Should be easy, right? Just throw the numbers at the chip and let it rip!

Running neural networks fast is like trying to cook a five-course meal in a kitchen where the fridge is three blocks away, you only have one pan, and every ingredient weighs 500 pounds. The math itself isn't the biggest problem; it's everything else.

Most chips were designed to run Microsoft Word, not neural networks. Your CPU was built thinking it would spend its life running if-statements, loops, and occasionally calculating your taxes (the one computation that even supercomputers find emotionally draining). It's optimized for sequential operations: do this, then that, then the other thing.

But neural networks are completely different. They want to do EVERYTHING AT ONCE. During training, you're updating millions of weights based on how wrong your predictions were. During inference (actually using the trained model), you're pushing data through millions of calculations simultaneously. Imagine you need to multiply a million numbers by another million numbers. Your CPU, bless its heart, wants to do them one at a time, like a very fast but very methodical accountant.

This is why GPUs became the backbone of AI computing. GPUs were designed for video games, where you need to calculate the color of millions of pixels simultaneously. Turns out, calculating pixel colors and doing neural network math are surprisingly similar: both involve doing the same operation on massive amounts of data in parallel.

But even GPUs aren't perfect for neural networks. That's why companies are now building specialized AI chips (TPUs, NPUs, and every other acronym ending in PU). These chips are designed from the ground up with one job: make neural networks go fast. They're like hiring a chef who only knows how to cook one dish, but they cook it at superhuman speed. While your CPU struggles through matrix operations sequentially and your GPU handles them pretty well in parallel, these specialized chips eat matrices for breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

In modern neural network computation, we spend more time and energy MOVING data than actually COMPUTING with it.

Think of your computer chip like a brilliant mathematician who works at lightning speed, but all their reference books are stored in different buildings across town. They can solve any equation instantly, but first, they need to get the numbers, and that journey takes forever.

Your chip can multiply two numbers in one clock cycle (remember, that's one of those billions of beats per second). Lightning fast! But getting those numbers from memory to the chip? That might take HUNDREDS of cycles. It's like your mathematician can solve a problem in one second, but needs five minutes to walk to the library and back.

The reason is distance (and space). Electricity moves fast, but not infinitely fast. The farther the data has to travel on the chip, the longer it takes. Computer designers solved this by creating a hierarchy of memory, like having multiple storage locations at different distances:

The exact structures vary, your phone's chip might skip L3 cache, while a server CPU might have massive amounts of it. The principle, however, remains the same: closer memory is faster but smaller.

Now here's where it gets painful for neural networks. Imagine your Ultralytics YOLO model has 50 million parameters (ChatGPT has billions, by the way). That's 50 million numbers that need to travel from memory to compute units and back. Even if each number is just 4 bytes, that's 200 megabytes of data that needs to move through your system.

The chip might process each number in a single cycle, but if it takes 100 cycles to fetch that number from RAM, you're spending 99% of your time waiting for delivery. It's like having a Formula 1 race car in a traffic jam. All that computational power, sitting there, waiting for data to arrive.

Here's the crucial insight: this is THE bottleneck in modern computing. It’s called the von Neumann bottleneck. Making chips faster at math is relatively easy. Making memory faster is hitting physical limits. This is why almost ALL performance optimization in AI happens at the memory level. When engineers speed up neural networks, they're rarely making the math faster; they're finding clever ways to move data less, cache it better, or access it smarter.

Modern AI chips don't just focus on compute speed; they obsess over memory bandwidth and data movement strategies. They pre-fetch data, reuse values already in cache, and organize computations to minimize memory trips. The winners in the AI hardware race aren't the ones with the fastest calculators; they're the ones who figured out how to keep those calculators fed with data. The entire game is about optimizing memory access patterns.

Every time you move a bit of data, you burn energy. Not much, we're talking picojoules, but when you're moving terabytes per second, it adds up FAST. In fact, moving data 1mm across a chip uses more energy than doing the actual computation!

This is why your laptop sounds like a jet engine when training neural networks. It's not the math that's generating heat; it's the data movement. Every parameter update, every gradient calculation, every forward pass is literally heating up your room.

Modern AI accelerators are basically exercises in thermodynamics. How much computation can we pack in before the chip melts? How fast can we move heat away? It's like overclocking, but the clock is always at 11, and we're just trying not to start a fire.

The fastest neural networks aren't necessarily the smartest, they're the ones designed with chips in mind. They:

It's like the difference between a recipe that says "use ingredients from your local grocery store" versus one that requires you to import spices from Tibet, cheese from France, and water from Antarctica. Both might taste good, but one is definitely more practical.

And this is why making neural networks go fast is an art form. It's not enough to have good math; you need to understand the hardware, respect the memory hierarchy, and dance perfectly with the architecture.

Welcome to the world where computer science meets physics meets engineering meets pure wizardry. Where moving a number costs more than computing with it. Where parallel is fast, but synchronization is death. Where your biggest enemy isn't complexity, it's distance.

When you train a YOLO model, you get a neural network that works beautifully on your training setup. But here's the thing: your gaming GPU, your iPhone, and that tiny chip in a security camera all speak completely different languages. They have different strengths, different weaknesses, and very different ideas about how to process data.

Think of it this way: a GPU has thousands of cores that can all work simultaneously – it's built for parallel processing. Meanwhile, a mobile chip might have special circuits designed specifically for AI operations, but can only handle certain types of math. And that edge device in your doorbell camera? It's trying to run AI on a power budget smaller than an LED lightbulb.

At Ultralytics, we support over a dozen different export formats because each one is optimized for different hardware. It's not about having too many options. It's about having the right option for YOUR specific needs.

In the original YOLO model, many operations happen in sequence. For example, we might do a convolution, then normalize the results, then apply an activation function. That's three separate steps, each requiring its own memory reads and writes.

But here's the clever bit: we can combine these operations into a single step. When we export YOLO for deployment, we fuse these operations together. Instead of:

We do:

For a typical YOLO model processing a 640×640 image, this simple trick eliminates gigabytes of unnecessary memory transfers. On a mobile phone, that's the difference between smooth real-time detection and frustrating lag.

YOLO doesn't actually need super-precise numbers to detect objects accurately. During training, we use 32 bits to represent each weight – that's like using a scientific calculator to measure ingredients for a sandwich. For actual deployment? 8 bits work just fine.

This is called quantization, and it's one of our most powerful optimization techniques. By using smaller numbers:

Not all layers in YOLO are equally sensitive to this reduction. The early layers that detect basic edges and shapes? They're robust – we can use 8-bit numbers without any problems. The final detection layers that determine "is this a cat or a dog?" need a bit more precision. So we adjust the precision layer by layer, using just enough bits to maintain accuracy while maximizing speed.

We've found that with careful quantization, Ultralytics YOLO maintains 99.5% of its original accuracy while running 3x faster on phones. That's the difference between a research model and something you can actually use in the real world.

There are dozens of different ways to perform the same mathematical operation. A simple convolution (the core operation in YOLO) can be computed using completely different algorithms, and the best choice depends on your specific hardware and input size.

When we export YOLO, our optimization framework actually tests different algorithms and picks the fastest one for your specific case. It's like having multiple routes to the same destination and choosing based on current traffic conditions. On a GPU, we might use an algorithm that processes many pixels simultaneously. On a CPU, we might use one that's optimized for sequential processing. The math is the same, but the execution strategy is completely different.

Remember how we talked about memory being the real bottleneck in modern computing? This is especially true for YOLO. The model might have 50 million parameters, and during inference, it creates gigabytes of intermediate results. Moving all this data around is often slower than the actual computation.

We use several tricks to minimize memory movement:

Smart Scheduling: We arrange operations so that data is used immediately while it's still in fast cache memory. For YOLO's feature pyramid network, this reduces memory traffic by 40%.

Tiling: Instead of processing an entire image at once, we break it into smaller tiles that fit in cache. This means the processor can work with fast, local memory instead of constantly fetching from slow main memory.

Buffer Reuse: Rather than constantly creating new memory for intermediate results, we reuse the same memory buffers. It's incredibly efficient – YOLO's entire backbone can run with just a bunch of reusable buffers.

Here's a surprising fact: YOLO models are often overengineered. We can remove 30% of the channels in many layers with virtually no impact on accuracy. This isn't just making the model smaller – it's making it faster, because there are literally fewer computations to perform.

The process is elegant: we analyze which parts of the network contribute least to the final detection results, remove them, and then fine-tune the model to compensate. A pruned YOLO11m model can be 30% faster while maintaining 99% of its original accuracy. On battery-powered devices, this efficiency gain can mean hours of extra operation time.

Different processors are good at different things, and the performance differences are staggering. The same YOLO11n model takes:

These aren't just speed differences from clock rates – they reflect fundamental architectural differences. GPUs have thousands of cores that work in parallel, perfect for YOLO's convolutions. Mobile NPUs have specialized circuits designed specifically for neural networks. CPUs are jack-of-all-trades, flexible but not specialized.

The key to optimization is matching YOLO's operations to what each chip does best. A GPU loves doing the same operation on lots of data simultaneously. A mobile NPU might only support certain operations but executes them incredibly efficiently. An edge TPU only works with 8-bit integers but achieves remarkable speed within that constraint.

When you export a YOLO model, something remarkable happens behind the scenes. We don't just convert the file format – we actually compile the model specifically for your target hardware. This is like the difference between Google Translate and a native speaker. The compilation process:

The compiler might reorganize operations to better use your processor's cache, select specialized instructions that your chip supports, or even use machine learning to find the best optimization strategy. Yes, we're using AI to optimize AI – the future is here!

This compilation step can make a 10x difference in performance. The same YOLO model might crawl along with generic code but fly with properly optimized instructions.

Let's talk about what happens when YOLO meets the real world – specifically, the challenging world of edge devices. Imagine a security camera that needs to run YOLO 24/7 for object detection. It faces brutal constraints:

Here's what optimization achieves in practice. A security camera running YOLO11s:

We reduced power consumption by 80% while actually improving performance! That's the difference between a device that overheats and drains batteries versus one that runs reliably for years.

The key is choosing the right trade-offs. On edge devices, we often:

At Ultralytics, we follow a systematic approach to optimization. First, we profile the model to understand where time is actually spent. Often, the bottlenecks aren't where you'd expect. Maybe 80% of the time is spent in just a few layers, or memory transfers are dominating computation time.

Next, we apply optimizations iteratively:

For example, with YOLO11m deployment on a phone:

Each step improves performance while maintaining over 99% of the original accuracy. The result? Real-time object detection on a device that fits in your pocket.

Modern devices are getting smarter about using multiple processors together. Your phone doesn't just have one processor – it has several, each specialized for different tasks:

The future of YOLO optimization is about intelligently splitting the model across these processors. Maybe the NPU handles the main convolutions, the CPU does the final detection logic, and the GPU visualizes the results. Each processor does what it's best at, creating a pipeline that's more efficient than any single processor could achieve.

We're developing smart partitioning algorithms that automatically figure out the best way to split YOLO across available processors, considering not just their capabilities but also the cost of moving data between them.

Optimizing YOLO models isn't just about converting file formats; it's about transforming cutting-edge AI into something that actually works in the real world. Through techniques like quantization (using smaller numbers), pruning (removing unnecessary parts), operation fusion (combining steps), and smart memory management, we achieve 10-100x performance improvements while maintaining accuracy.

The remarkable thing? There's no universal "best" optimization. A cloud server with unlimited power needs different optimizations than a battery-powered drone. A phone with a dedicated AI chip needs different treatment than a Raspberry Pi. That's why Ultralytics provides so many export options – each one is optimized for different scenarios.

Every optimization we've discussed serves one goal: making computer vision accessible everywhere. Whether you're building a smart doorbell, a drone application, or a massive cloud service, we provide the tools to make YOLO work within your constraints.

When you export a YOLO model with Ultralytics, you're not just saving a file. You're leveraging years of research in making neural networks practical. You're transforming a state-of-the-art AI model into something that can run on real hardware, with real constraints, solving real problems.

That's what we do at Ultralytics. We bridge the gap between AI research and practical deployment. We make computer vision work everywhere, because the future of AI isn't just about having the best models – it's about making those models useful in the real world.