Why Ultralytics YOLO26 removes NMS and how that changes deployment

Discover how Ultralytics YOLO26 enables true end-to-end, NMS-free inference and why removing post-processing simplifies export and edge deployment.

Discover how Ultralytics YOLO26 enables true end-to-end, NMS-free inference and why removing post-processing simplifies export and edge deployment.

On January 14, we launched Ultralytics YOLO26, the latest generation of our computer vision models. With YOLO26, our goal was not just to improve accuracy or speed, but to rethink how object detection models are built and deployed in real-world systems.

As computer vision moves from research into production, models are increasingly being expected to run on CPUs, edge devices, cameras, robots, and embedded hardware. In these environments, reliability, low latency, and ease of deployment matter just as much as performance.

YOLO26 was designed with this reality in mind, using a streamlined end-to-end architecture that removes unnecessary complexity from the inference pipeline. One of the most important innovations made in YOLO26 is the removal of Non-Maximum Suppression, commonly known as NMS.

For years, NMS has been a standard part of object detection systems, used as a post-processing step to clean up duplicate detections. While effective, it also introduced extra computation and deployment challenges, especially on edge hardware.

With YOLO26, we took a different approach. By rethinking how predictions are generated and trained, we enable true end-to-end, NMS-free inference. The model produces final detections directly, without relying on external cleanup steps or handcrafted rules. This makes YOLO26 faster, easier to export, and more reliable to deploy across a wide range of hardware platforms.

In this article, we’ll take a closer look at why traditional object detection relied on NMS, how it became a deployment bottleneck, and how YOLO26 eliminates the need for workarounds. Let's get started!

Before we dive into what NMS is and why we removed it in YOLO26, let’s take a step back and look at how traditional object detection models generate their predictions.

Traditional object detection models often produce multiple overlapping bounding boxes for the same object. Each of these boxes comes with its own confidence score, even though they all refer to the same object in the image.

This happens for a few reasons. First, the model makes predictions at many spatial locations and at different scales at the same time. This helps the model detect objects of different sizes, but it also means that nearby locations can all identify the same object independently.

Second, many object detection systems use anchor-based approaches, which generate a large number of candidate boxes around each location. While this improves the chance of finding objects accurately, it also increases the number of overlapping predictions.

Finally, grid-based detection itself naturally leads to redundancy. When an object sits near the boundary of multiple grid cells, several cells may predict a box for that object, resulting in multiple overlapping detections.

Because of this, the raw output of the model often contains several boxes for a single object. To make the results usable, these redundant predictions need to be filtered so that only one final detection remains.

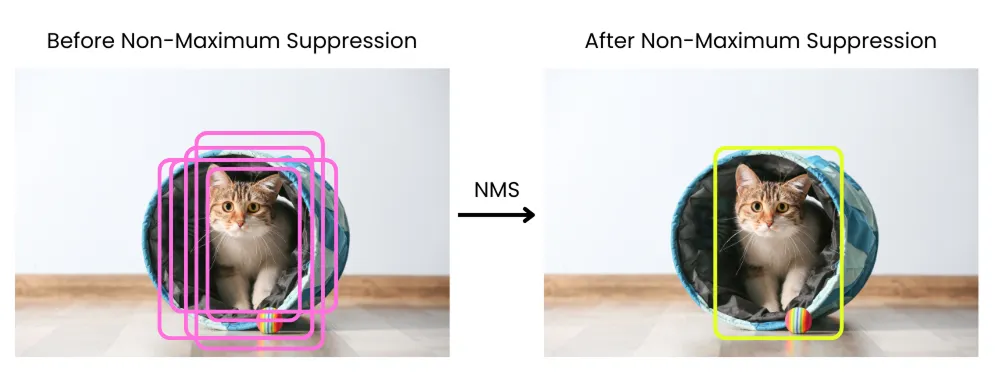

Once an object detection model produces multiple overlapping bounding boxes for the same object, those results need to be cleaned up before they can be used. This is where Non-Maximum Suppression is applied.

Non-Maximum Suppression is a post-processing step that runs after the model has finished making its predictions. Its purpose is to reduce duplicate detections so that each object is represented by a single final bounding box.

The process works by comparing bounding boxes based on their confidence scores and how much they overlap. Predictions with very low confidence are removed first.

The remaining boxes are then sorted by confidence, and the box with the highest score is selected as the best detection. That selected box is compared with the other boxes.

If another box overlaps too much with it, that box is suppressed and removed. Overlap is typically measured using Intersection over Union, a metric that calculates the ratio between the area shared by two boxes and the total area covered by both. This process repeats until only the most confident, non-overlapping detections remain.

While Non-Maximum Suppression helps filter duplicate detections, it also introduces challenges that become more visible once models move out of research and into real-world deployment.

One of the biggest issues is performance. NMS runs after inference and requires comparing bounding boxes with each other to decide which ones to keep.

This process is computationally expensive and difficult to parallelize efficiently. On edge devices and CPU-based systems, this extra work can add noticeable latency, making it harder to meet real-time requirements.

NMS also increases deployment complexity. Because it isn't part of the model itself, it has to be implemented separately as post-processing code.

Different runtimes and platforms handle NMS in different ways, which often means maintaining custom implementations for each target environment. What works in one setup may behave slightly differently in another, making deployment more fragile and harder to scale.

Hardware optimization is another challenge. NMS doesn't map cleanly to specialized AI accelerators, which are designed to run neural network operations efficiently. As a result, even when the model runs quickly on optimized hardware, NMS can become a bottleneck that limits overall performance.

In addition to these factors, NMS relies on manually chosen parameters such as confidence thresholds and overlap thresholds. These settings can affect results significantly and often need to be tuned for different datasets, applications, or hardware. This makes behavior less predictable in production systems and adds extra configuration overhead.

The limitations of Non-Maximum Suppression led us to rethink how object detection models should behave at inference time. Instead of generating many overlapping predictions and cleaning them up afterward, we asked a more fundamental question.

What if the model could produce final detections directly? This question sits at the core of end-to-end object detection inference. In an end-to-end system, the model is trained to handle the entire detection process from start to finish, without relying on external cleanup steps.

Rather than producing many candidate boxes and filtering them after inference, the model learns to generate a small set of confident, non-overlapping predictions on its own. Duplicate detections are resolved inside the network instead of being removed by post-processing.

Newer model architectures showed that this approach was both possible and practical. With the right training strategy, models could learn to associate each object with a single prediction instead of many competing ones, reducing redundancy at its source.

For this to work, training has to change as well. Instead of letting many predictions compete for the same object, the model learns to make one clear decision, producing fewer and more confident detections.

The overall result is a simpler inference pipeline. Because duplicates are already resolved internally, there is no need for Non-Maximum Suppression at inference time. The model output is already the final set of detections.

This end-to-end design also makes deployment easier. Without post-processing steps or platform-specific NMS implementations, the exported model is fully self-contained and behaves consistently across different inference frameworks and hardware targets.

As our Lead Partnership Engineer, Francesco Mattioli explains, “True end-to-end learning means the model should handle everything from pixels to predictions, without handcrafted post-processing steps that break differentiability and complicate deployment.”

YOLO26 removes Non-Maximum Suppression by changing how detections are learned and produced, rather than relying on post-processing to clean them up. Instead of allowing many predictions to compete for the same object, YOLO26 is trained to learn a clear one-to-one relationship between objects and outputs.

This is enabled in part by learnable query-based detection, which helps the model focus on producing a single, confident prediction for each object rather than many overlapping candidates. Each object is associated with one prediction, naturally reducing duplicate detections.

This behavior is reinforced through consistent matching strategies during training, encouraging the model to make one confident decision per object rather than generating overlapping predictions. Ultimately, the model produces fewer predictions, but each one represents a final detection.

Another important innovation that enables NMS-free inference in YOLO26 is the removal of Distribution Focal Loss, or DFL. In earlier YOLO models, DFL was used to improve bounding box regression by predicting a distribution of possible box locations rather than a single value.

While this approach improved localization accuracy, it also added complexity to the detection pipeline. That complexity became a limitation when moving toward true end-to-end inference.

DFL introduced additional computation and fixed regression ranges, which made it harder for the model to learn clean, one-to-one object assignments and increased reliance on post-processing steps like Non-Maximum Suppression. With YOLO26, we removed DFL and redesigned bounding box regression to be simpler and more direct.

Instead of relying on distribution-based outputs, the model learns to predict accurate box coordinates in a way that supports fewer, more confident detections. This change helps reduce overlapping predictions at their source and aligns bounding box regression with YOLO26’s end-to-end, NMS-free design.

An NMS-free design makes YOLO26 a truly end-to-end model. This has an important impact on exporting models.

Exporting means converting a trained model into a format that can run outside the training environment, such as ONNX, TensorRT, CoreML, or OpenVINO. In traditional pipelines, this process often breaks down because Non-Maximum Suppression isn't part of the model itself.

By removing NMS, YOLO26 avoids this problem entirely. The exported model already includes everything needed to produce final detections.

This makes the exported model fully self-contained and more portable across inference frameworks and hardware targets. The same model behaves consistently whether it is deployed on servers, CPU-only systems, embedded devices, or edge accelerators. Deployment becomes more straightforward because what you export is exactly what you run.

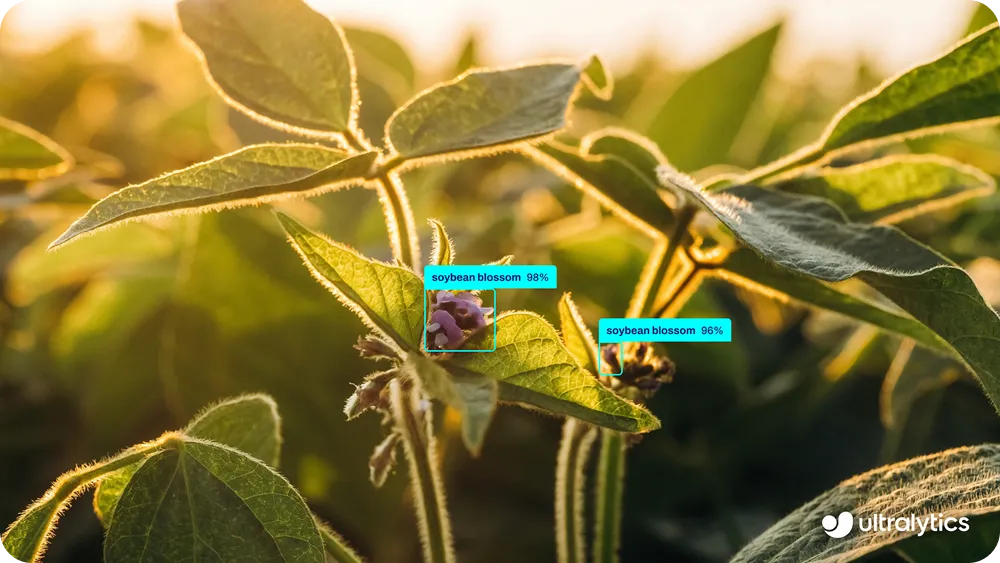

This simplicity is especially important for edge applications. For example, YOLO26 can be easily deployed on devices like drones for use cases such as crop monitoring, field inspection, and plant health analysis, where limited compute and power budgets make complex post-processing pipelines impractical. Because the model outputs final detections directly, it runs reliably on lightweight hardware without extra processing steps.

In short, NMS-free inference removes friction from exporting and deployment and enables cleaner, more reliable vision systems. NMS was a workaround. YOLO26 doesn’t need workarounds anymore.

YOLO26 removes Non-Maximum Suppression by solving the underlying problem of duplicate detections, rather than cleaning them up after the fact. Its end-to-end design allows the model to produce final detections directly, making export and deployment simpler and more consistent across different hardware. NMS was a useful workaround for earlier systems, but YOLO26 no longer needs it.

Join our community and check out our GitHub repository to learn more about AI. Explore our solutions pages on AI in agriculture and computer vision in retail. Discover our licensing options and get started with Vision AI today!