Learn how monocular depth estimation works, how it compares to sensor-based depth methods, and how it enables scalable 3D perception in vision systems.

Learn how monocular depth estimation works, how it compares to sensor-based depth methods, and how it enables scalable 3D perception in vision systems.

Self-driving cars are designed to understand what’s happening around them so they can drive safely. This means going beyond simply recognizing objects like pedestrians or other vehicles.

They also need to know how far away those objects are in order to respond correctly. However, giving machines this sense of distance isn’t straightforward. Unlike humans, they don't naturally perceive depth from images and have to be explicitly taught how to do so.

One reason behind this is that most cameras capture the world as flat, two-dimensional images. Turning those images into something that reflects real-world depth and 3D structure is tricky, especially when systems need to work reliably in everyday conditions.

Interestingly, computer vision, which is a branch of AI that focuses on interpreting and understanding visual data, makes it possible for machines to better understand the world from images. For instance, monocular depth estimation is a computer vision technique that estimates the distance of objects using only a single camera image.

By learning visual cues such as object size, perspective, texture, and shading, these models can predict depth without relying on additional sensors like LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) or stereo cameras. In this article, we’ll explore what monocular depth estimation is, how it works, and some of its real-world applications. Let’s get started!

Monocular depth estimation enables a machine to understand how far objects are from it using just a single image. Since it relies on only one camera, this approach has several advantages, including lower cost and simpler hardware requirements.

For example, it can be used in affordable home robots that operate with a single camera. Even from a single image, the robotic system can identify which walls are closer and which doors are farther away, and infer the overall depth of the space.

Often, a single image doesn’t contain information at the correct scale, so monocular depth estimation generally focuses on relative depth. In other words, it can determine which objects are closer and which are farther away, even if the exact distances aren’t known.

When a model is trained on data with ground-truth distances or absolute depth, such as depth measurements from sensors like LiDAR, it can learn to predict distances in real-world units, such as meters. Without this kind of reference data, the model can still infer relative depth but can’t reliably estimate absolute distances.

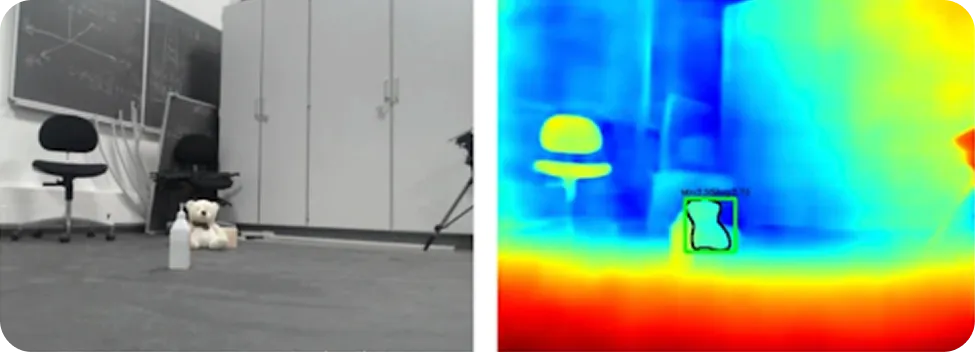

The output of monocular depth estimation is typically a depth map, which is an image where each pixel represents how near or far that part of the scene is. A depth map provides vision systems with a basic understanding of the 3D structure of the environment.

Depth estimation can be approached in several ways, depending on the available sensors, hardware constraints, and accuracy requirements. Traditional methods often rely on multiple viewpoints or specialized sensors to directly measure distance.

One common approach is stereo vision, which estimates depth by comparing two synchronized images captured from slightly different viewpoints. By measuring the difference between corresponding points in the two images, the system can infer how far objects are from the camera.

Another approach is RGB-D (Red, Green, Blue, and Depth) systems, which use active depth sensors to directly measure distance at each pixel. These systems can provide accurate depth information in controlled environments but require additional hardware.

Meanwhile, LiDAR-based methods use laser pulses to generate precise three-dimensional representations of a scene. While highly accurate, LiDAR sensors are often expensive and add significant hardware complexity.

In contrast, monocular depth estimation infers depth using only a single RGB image. Because it doesn't depend on multiple cameras or specialized sensors, it is easier to deploy at scale and is a good option when cost and hardware resources are limited.

When estimating depth from a single image, monocular depth models learn to recognize visual cues that humans use instinctively to judge distance. These cues include perspective lines, object size, texture density, object overlap, and shading, all of which provide hints about how far objects are from the camera.

These cues work together to create a sense of depth. Objects that appear smaller or are partially occluded are often farther away, while clearer details and larger visual appearances usually suggest that something is closer.

To learn these patterns, monocular depth models are trained on large-scale image datasets, often paired with depth information obtained from other sources such as LiDAR or stereo systems. During training, the models learn how visual cues relate to depth, allowing them to infer distance from a single image at inference time.

With diverse training data, modern vision models can generalize this learned understanding across a wide range of environments, including indoor and outdoor scenes, and can handle unfamiliar viewpoints.

Next, we’ll explore the main approaches used to estimate depth from a single image and how these methods have evolved over time.

Early depth estimation methods relied on straightforward visual rules tied to camera geometry. Cues like perspective, object size, and whether one object blocked another were used to estimate distance.

For instance, when two similar objects appeared at different sizes, the smaller one was assumed to be farther away. These approaches worked reasonably well in controlled environments where factors like lighting, camera position, and scene layout stayed consistent.

However, in real-world scenes, these assumptions often break down. Variations in lighting, viewpoint changes, and increased scene complexity can lead to unreliable depth estimates, limiting the effectiveness of classical methods in uncontrolled settings.

Early machine learning methods brought more flexibility to depth estimation by learning patterns directly from data. Instead of relying only on fixed geometric rules, these models tried to learn the relationship between visual information and distance, treating depth prediction as a regression problem based on cues like edges, textures, and color changes.

Selecting these features was a key part of the process. Engineers had to decide which visual signals to extract and how to represent them, and the model’s performance depended heavily on those choices.

While this approach worked better than earlier methods, it still had limits. If the selected features lacked important context, depth predictions were less accurate. As scenes became more complex and varied, these models often struggled to produce reliable results.

Most modern monocular depth estimation systems use deep learning, which refers to neural networks with many layers that can learn complex patterns from data. These models learn to predict depth directly from images and produce depth maps.

Many approaches are built using convolutional neural networks (CNNs), a type of neural network designed to process images by detecting patterns such as edges and shapes. These models often use an encoder–decoder setup: the encoder extracts visual features from the image, and the decoder converts those features into a depth map. Processing the image at multiple scales helps the model capture the overall layout of the scene while still capturing clear object boundaries.

More recent models focus on understanding relationships across different parts of an image. Transformer-based and Vision Transformer (ViT) models use attention mechanisms, which allow the model to identify which regions of an image are most relevant and to relate distant areas to each other. This helps the model build a more consistent understanding of depth across the entire scene.

Some systems combine both ideas. Hybrid CNN–Transformer models use CNNs to capture fine local details and Transformers to model the global context of the scene. While this often improves accuracy, it typically requires more computational resources, such as additional memory and processing power.

As you learn about monocular depth estimation, you might be wondering why depth understanding is such an important part of vision-based AI systems.

When a system can estimate how far away objects and surfaces are, it gains a better understanding of how a scene is laid out and how different elements relate to one another. This kind of spatial awareness is essential for making reliable decisions, especially in real-world applications like autonomous driving.

Depth information also adds valuable context to other computer vision tasks. For example, object detection, supported by models like Ultralytics YOLO26, can tell a system what is present in a scene, but depth helps answer where those objects are located relative to the camera and to each other.

Together, these capabilities enable a wide range of vision AI applications, such as building 3D maps, navigating complex environments, and understanding a scene as a whole.

Robots and autonomous vehicles depend on this information to move safely, avoid obstacles, and react to changes in real time. For instance, Tesla’s vision-only driving approach relies on camera images combined with depth estimation, rather than LiDAR, to understand how far away objects are and how they are positioned on the road.

Although model architectures vary, most monocular depth estimation models follow a similar process to convert a single image into a depth map. Here’s a quick overview of the key steps involved:

The process we just discussed assumes that we already have a trained or pre-trained model. But how does training a monocular depth estimation model actually work?

Training begins with preparing image data so it can be processed efficiently by the network. Input images are resized and normalized to a consistent scale, then passed through the model to generate a predicted depth map that estimates distance at each pixel.

The predicted depth map is then compared with reference depth data using a loss function, which measures how far the model’s prediction is from the ground-truth depth. This loss value represents the model’s current error and provides a signal for improvement.

An optimizer uses this signal to update the model by adjusting its internal weights. To do this, the optimizer computes the gradient, which describes how the loss changes with respect to each model parameter, and applies these updates repeatedly over multiple epochs, or full passes through the training dataset.

This iterative supervised learning training process is guided by hyperparameters such as the learning rate, which controls how large each update step is, and the batch size, which determines how many images are processed at once. Because training involves a large number of mathematical operations, it is typically accelerated using a graphics processing unit (GPU), which is great for parallel computation.

Once training is complete, the model is evaluated using standard evaluation metrics on a validation set, which consists of images that weren’t used during training. This evaluation helps measure how well the model generalizes to new data.

The trained model can then be reused or fine-tuned for new scenarios. Overall, this training process enables monocular depth estimation models to produce consistent depth estimates, which are essential for downstream tasks such as 3D reconstruction and real-world deployment.

Monocular depth estimation has improved rapidly as models have become better at understanding entire scenes rather than just small visual details. Earlier approaches often produced uneven depth maps, especially in complex environments.

Newer models, as seen in recent research published on arXiv, focus more on a global context, which leads to depth predictions that look more stable and realistic. Well-known models such as MiDaS and DPT helped drive this shift by learning depth from diverse, high-resolution datasets and generalizing well across many scenes.

More recent models, including ZoeDepth and Depth Anything V2, build on this work by improving scale consistency while maintaining strong performance across a wide range of settings. This type of progress is often measured using common benchmark datasets like KITTI and NYU, which cover both outdoor and indoor scenes.

Another clear trend is balancing accuracy with practicality. Smaller models are optimized for speed and can run in real time on edge or mobile devices, while larger models prioritize higher resolution and long-range depth accuracy.

Next, let’s walk through some real-world examples that show how monocular depth estimation is used to reason about the 3D structure of a scene from a single image.

In all of these cases, it’s important to keep in mind that the depth information is an estimate inferred from visual cues, not a precise measurement. This makes monocular depth estimation useful for understanding relative layout and spatial relationships, but not a replacement for sensors designed to measure distance accurately, such as LiDAR or stereo systems.

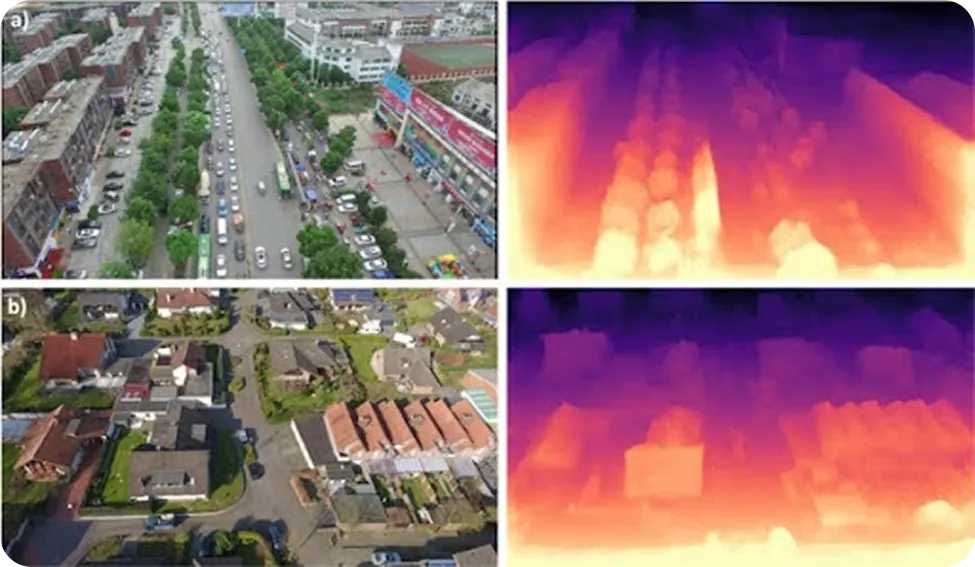

Drones often operate in environments where GPS signals are unreliable, such as forests, construction sites, disaster zones, or dense urban areas. To fly safely in these conditions, they need to understand the surrounding terrain and know how far away obstacles are. In the past, this typically required adding sensors like LiDAR or stereo cameras, which increase weight, power consumption, and overall cost.

Monocular depth estimation is a simpler alternative. Using just a single RGB camera, drones can estimate depth from images and build a basic 3D understanding of their environment. This lets them detect obstacles such as buildings, trees, or sudden changes in terrain and adjust their flight path in real time.

These depth estimates support key navigation tasks, including obstacle avoidance, altitude control, and safe landing. As a result, lightweight drones can perform mapping, inspection, and navigation tasks without relying on specialized depth sensors.

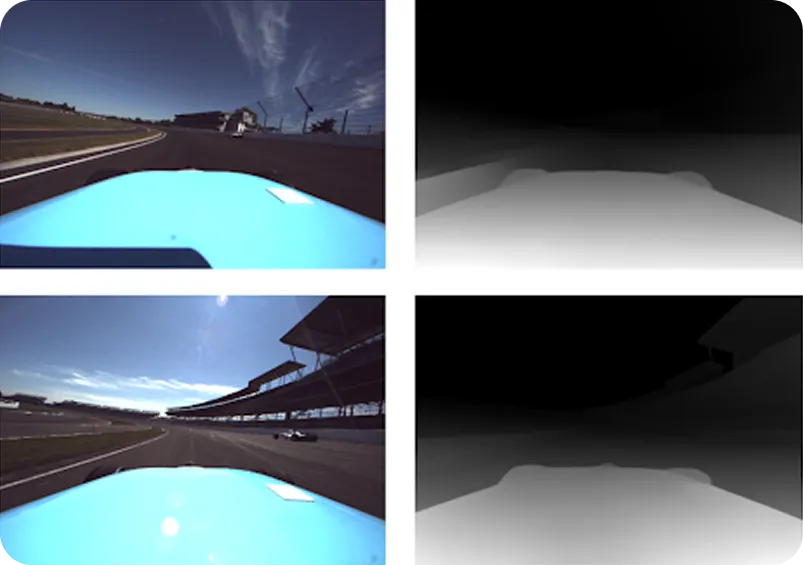

Autonomous vehicles typically rely heavily on LiDAR sensors, which use laser pulses to measure distance and build a 3D view of the road. While highly accurate, LiDAR can struggle with sharp road crests, steep slopes, occlusion, or sudden vehicle pitch, sometimes returning sparse or missing depth data.

Monocular depth estimation can help fill these gaps by providing dense depth information from a single RGB image, even when LiDAR data is incomplete. Consider a scenario where a self-driving car is approaching a hill crest at speed. LiDAR beams can overshoot the road beyond the crest, leaving uncertainty about what lies ahead.

Camera-based depth estimation, however, can still infer the shape of the road from visual cues such as perspective and texture, helping the vehicle maintain reliable perception until LiDAR data stabilizes. Together, LiDAR and monocular depth estimation enable more stable perception and safer control in challenging driving conditions.

Robots are often operated in places where detailed maps are unavailable, and conditions change constantly. To move safely, they need a reliable sense of how much space is around them and where obstacles are located.

Monocular depth estimation can provide this spatial awareness using a single RGB camera, without relying on heavy or expensive hardware. By learning visual cues such as scale and perspective, depth estimation models can generate dense depth maps of the surroundings. This gives robots a clear view of the distance to surfaces and objects.

In particular, when depth information is combined with computer vision tasks like object detection and semantic segmentation, robots can gain a more complete view of their environment. They can identify objects, understand their distance, and decide where it is safe to move. This supports obstacle avoidance, free-space detection, and real-time path planning.

Here are some of the main advantages of using monocular depth estimation:

While monocular depth estimation offers clear benefits, here are some limitations to consider:

While monocular depth estimation is an interesting area of research, it’s important to understand where it can practically be used and where it can’t be used. The distances it produces are estimates based on what the model sees in an image, not exact measurements taken from the real world.

Because of this, the quality of the results can change depending on factors like lighting, scene complexity, and how similar the scene is to what the model was trained on. Monocular depth estimation is usually good at telling what is closer and what is farther away, but it isn’t reliable when you need exact distances.

In situations where precision really matters, such as safety-critical systems, industrial inspection, or robots that need to interact very precisely with objects, depth needs to be measured directly. Sensors like LiDAR, radar, stereo cameras, or structured-light systems are designed for this and provide much more dependable distance information.

Monocular depth estimation can also struggle in visually difficult conditions. Poor lighting, strong shadows, reflective or transparent surfaces, fog, smoke, or scenes with very little visual texture can all make depth estimates less reliable. Estimating depth at long distances is another case where dedicated sensors usually work better.

When it comes to real-world solutions, monocular depth estimation works best as a supporting tool rather than a standalone solution. It can add useful spatial context, help fill in gaps when other sensors are limited, and improve overall scene understanding. However, it shouldn’t be the only source of depth information when accuracy, safety, or strict reliability requirements are important.

Monocular depth estimation is a computer vision technique that enables machines to estimate how far objects are using only a single camera image. By learning visual cues such as perspective, object size, texture, and shading, these AI models can infer the 3D structure of a scene without relying on sensors like LiDAR or stereo cameras. This makes monocular depth estimation a cost-effective and scalable approach for applications such as autonomous driving, robotics, and 3D scene understanding.

To explore more about Vision AI, visit our GitHub repository and join our community. Check out our solution pages to learn about AI in robotics and computer vision in manufacturing. Discover our licensing options to get started with computer vision today!