Hộp neo

Tìm hiểu cách các hộp neo hoạt động như các mẫu tham chiếu cho việc phát hiện đối tượng. Khám phá cách chúng cải thiện độ chính xác và cách các mô hình như... Ultralytics YOLO26 sử dụng thiết kế không cần neo.

Các hộp neo là các hình chữ nhật tham chiếu được xác định trước với tỷ lệ khung hình và kích thước cụ thể, được đặt trên một hình ảnh để hỗ trợ các mô hình phát hiện đối tượng trong việc định vị và phân loại đối tượng. Thay vì yêu cầu mạng nơ-ron dự đoán kích thước và vị trí chính xác của một đối tượng từ đầu—điều này có thể không ổn định do sự đa dạng về hình dạng của đối tượng—mô hình sử dụng các mẫu cố định này làm điểm xuất phát. Bằng cách học cách dự đoán mức độ điều chỉnh, hay "hồi quy", các hộp ban đầu này để phù hợp với dữ liệu thực tế, hệ thống có thể đạt được sự hội tụ nhanh hơn và độ chính xác cao hơn. Kỹ thuật này đã thay đổi căn bản lĩnh vực thị giác máy tính (CV) bằng cách đơn giản hóa nhiệm vụ định vị phức tạp thành một bài toán tối ưu hóa dễ quản lý hơn.

Cơ chế hoạt động của hộp neo

Trong các bộ dò dựa trên neo cổ điển, ảnh đầu vào được chia thành một lưới các ô. Tại mỗi vị trí ô, mạng tạo ra nhiều hộp neo với hình dạng khác nhau. Ví dụ, để đồng thời detect Với một người đi bộ cao và một chiếc xe hơi rộng, mô hình có thể đề xuất một hình hộp cao, hẹp và một hình hộp ngắn, rộng tại cùng một điểm trung tâm.

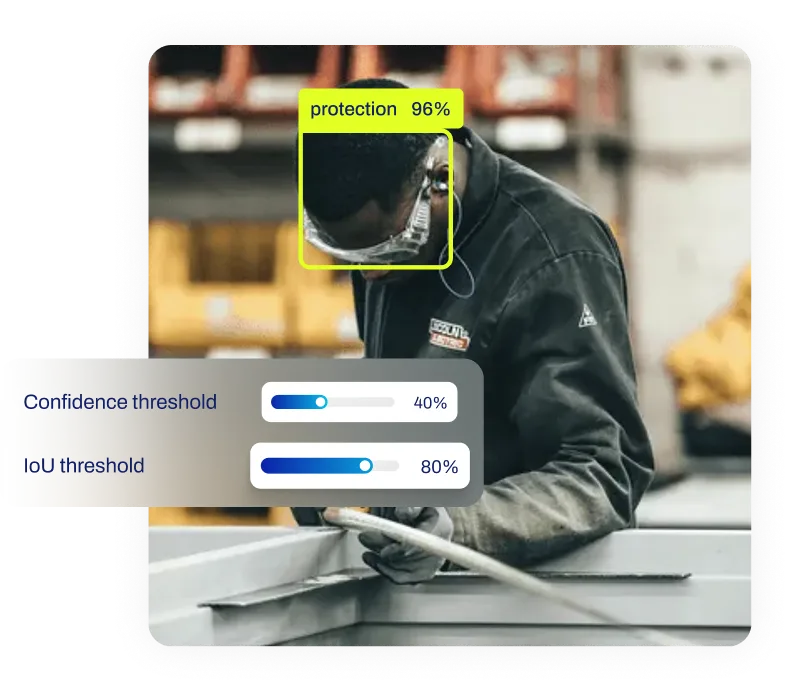

Trong quá trình huấn luyện mô hình , các anchor này được so khớp với các đối tượng thực tế bằng cách sử dụng một chỉ số gọi là Intersection over Union ( IoU ) . Các anchor trùng lặp đáng kể với một đối tượng được gắn nhãn sẽ được chỉ định là các mẫu "tích cực". Sau đó, mạng sẽ học hai nhiệm vụ song song:

-

Phân loại: Thuật toán này gán một điểm xác suất cho phần tử neo, cho biết khả năng phần tử đó chứa một lớp cụ thể (ví dụ: "chó" hoặc "xe đạp"). Nó sử dụng các mục tiêu học có giám sát tiêu chuẩn như hàm mất mát entropy chéo.

-

Hồi quy hộp: Phương pháp này tính toán các giá trị bù chính xác (dịch chuyển tọa độ và hệ số tỷ lệ) cần thiết để biến đổi điểm neo chung thành một hộp giới hạn vừa khít.

Cách tiếp cận này cho phép mô hình xử lý nhiều đối tượng có kích thước khác nhau nằm gần nhau, vì mỗi đối tượng có thể được gán cho điểm neo phù hợp nhất với hình dạng của nó.

Các Ứng dụng Thực tế

Mặc dù các kiến trúc mới hơn đang hướng tới thiết kế không cần neo, hộp neo vẫn rất quan trọng trong nhiều hệ thống sản xuất hiện có, nơi các đặc tính của vật thể có thể dự đoán được.

-

Quản lý bán lẻ và tồn kho: Trong các giải pháp bán lẻ dựa trên AI , camera giám sát hàng hóa trên kệ. Vì các sản phẩm như hộp ngũ cốc hoặc lon nước ngọt có kích thước tiêu chuẩn, nên các hộp trưng bày chính có thể được điều chỉnh theo tỷ lệ kích thước cụ thể này. Kiến thức có sẵn này giúp mô hình duy trì khả năng ghi nhớ cao ngay cả trong môi trường lộn xộn.

-

Lái xe tự hành: Hệ thống nhận thức trong xe tự hành dựa trên việc phát hiện người đi bộ, phương tiện giao thông và biển báo giao thông. Vì một chiếc xe nhìn từ xa có hình dạng tương đối nhất quán so với mặt đường, nên việc sử dụng các điểm neo được thiết kế riêng cho các hình dạng này đảm bảo khả năng theo dõi đối tượng và ước lượng khoảng cách chính xác.

Dựa trên neo so với không neo

Điều quan trọng là phải phân biệt giữa các phương pháp dựa trên neo truyền thống và các bộ dò không dựa trên neo hiện đại.

-

Dựa trên điểm neo: Các mô hình như Faster R-CNN gốc hoặc các phiên bản đầu tiên. YOLO các phiên bản (ví dụ, YOLOv5 Chúng sử dụng các mẫu được định sẵn này. Chúng mạnh mẽ nhưng thường yêu cầu điều chỉnh thủ công các siêu tham số (kích thước/tỷ lệ neo) hoặc các thuật toán phân cụm như phân cụm k-means để thích ứng với các tập dữ liệu mới.

-

Không cần neo (Anchor-Free): Các mô hình tiên tiến, bao gồm YOLO26 , thường sử dụng phương pháp không cần neo hoặc phương pháp từ đầu đến cuối. Các mạng này dự đoán trực tiếp tâm đối tượng hoặc các điểm mấu chốt, loại bỏ nhu cầu cấu hình neo thủ công. Điều này đơn giản hóa kiến trúc và tăng tốc độ suy luận bằng cách loại bỏ việc tính toán cần thiết để xử lý hàng ngàn neo nền trống.

Ví dụ: Truy cập thông tin neo

Mặc dù các API cấp cao hiện đại như Nền tảng Ultralytics đã trừu tượng hóa các chi tiết này trong quá trình huấn luyện, việc hiểu về các anchor vẫn hữu ích khi làm việc với các kiến trúc mô hình cũ hơn hoặc phân tích các tệp cấu hình mô hình. Đoạn mã sau đây minh họa cách tải một mô hình và kiểm tra cấu hình của nó, nơi các thiết lập anchor (nếu có) thường được định nghĩa.

from ultralytics import YOLO

# Load a pre-trained YOLO model (YOLO26 is anchor-free, but legacy configs act similarly)

model = YOLO("yolo26n.pt")

# Inspect the model's stride, which relates to grid cell sizing in detection

print(f"Model strides: {model.model.stride}")

# For older anchor-based models, anchors might be stored in the model's attributes

# Modern anchor-free models calculate targets dynamically without fixed boxes

if hasattr(model.model, "anchors"):

print(f"Anchors: {model.model.anchors}")

else:

print("This model architecture is anchor-free.")

Những thách thức và cân nhắc

Mặc dù hiệu quả, các hộp neo (anchor boxes) lại làm tăng độ phức tạp. Số lượng lớn các hộp neo được tạo ra—thường lên đến hàng chục nghìn hộp cho mỗi hình ảnh—tạo ra vấn đề mất cân bằng lớp, vì hầu hết các hộp neo chỉ bao phủ nền. Các kỹ thuật như Focal Loss được sử dụng để giảm thiểu điều này bằng cách giảm trọng số các ví dụ nền dễ nhận diện. Ngoài ra, kết quả cuối cùng thường yêu cầu Non-Maximum Suppression ( NMS ) để lọc ra các hộp trùng lặp dư thừa, đảm bảo chỉ giữ lại phát hiện đáng tin cậy nhất cho mỗi đối tượng.

.webp)